PVC Security: An Intermediary-free Solution to Safe Data Sharing Between Rational Parties

This article is part of the Academic Alibaba series and is taken from the paper entitled “Covert Security with Public Verifiability: Faster, Leaner, and Simpler” by Cheng Hong, Jonathan Katz, Vladimir Kolesnikov, Wen-jie Lu and Xiao Wang. The full paper can be read here.

How can mutually mistrustful parties collaborate to reap the full value of their collective data?

This is a pertinent question in the Big Data era. Powerful computing capabilities offer the potential to extract all sorts of valuable insights from data, valuable enough that some are even claiming data is the new oil. But just like oil, data cannot generate value unless it flows.

Most data does not flow, because most firms have a highly cautious attitude toward data sharing. They are right to do so, due to data confidentiality and personal privacy concerns, but this means that mutually mistrustful parties are denied insights that could be produced by analyzing their data jointly.

Since nobody is expecting competing enterprises to resolve their differences any time soon, the problem boils down to a technical one: how to enable parties to perform computations over their joint data without violating privacy. The solution is to use Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC) protocols.

An international research team with members from Alibaba and several US and Japanese universities has proposed a new MPC protocol that offers something called publicly verifiable covert (PVC) security. PVC security requires zero trust between parties; rather, it exploits the assumption that neither party wants to be caught cheating. It does this by generating (with high probability) a publicly verifiable certificate of misbehavior if any party attempts to break the rules, permanently exposing that party’s untrustworthiness to the world.

Other approaches to PVC have failed to catch on due to their high overhead, large certificates, and general complexity. The researchers’ faster, leaner, simpler approach is the first truly viable solution. The world-renowned International Association for Cryptologic Research has recognized the significance of the research by accepting the paper describing the protocol to their flagship Eurocrypt conference in 2019.

But why is a certificate of poor trustworthiness necessary in the first place? The simple answer is that while all security protocols attempt to make it impossible to break the rules to begin with, they are limited in how efficiently they can do this. Protocols with “semi-honest security” provide security only as long as all parties stick to the rules of the protocol, while those in the “malicious security” category protect against the most devious attacks—but are extremely inefficient to implement.

PVC security, the team claims, is the best of both worlds. It is a form of malicious security that protects implements the certificate mechanism to disincentivize or penalize attackers.

To understand how the team arrived at this technical compromise, it is necessary to go back to where both semi-honest and malicious security models began: the basics of MPC.

Secure Multi-party Computation

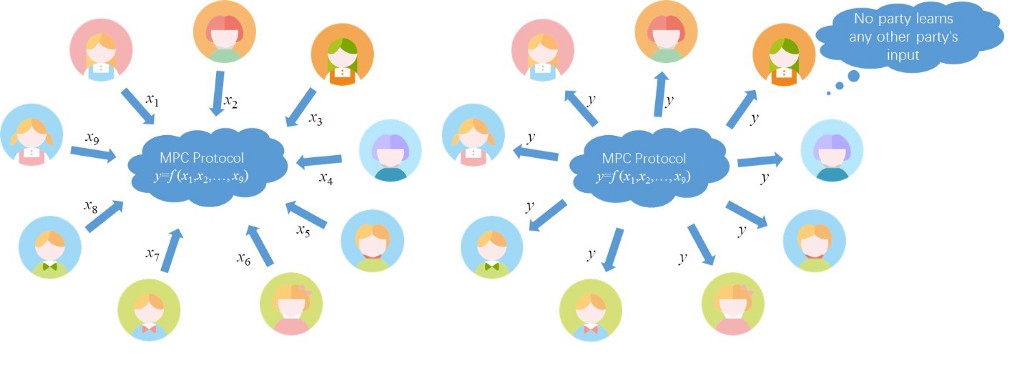

In 1986, Chinese Academician Andrew Chi-Chih Yao proposed a method of secure multi-party computation (MPC) for performing calculations on behalf of multiple mutually distrusting parties. MPC allows each party to provide their input and receive the final output without seeing the input of the other parties. In principle, this provides a way of deriving value from data without having to disclose that data to a third party.

There are two primary ways of implementing MPC: garbled circuit (GC) and secret sharing. The solution adopted by the research team is based on GC.

Garbled circuit

Any function is ultimately represented by circuits (adders, multipliers, shifters, selectors, etc.), and these circuits can be composed of only AND and XOR logic gates.

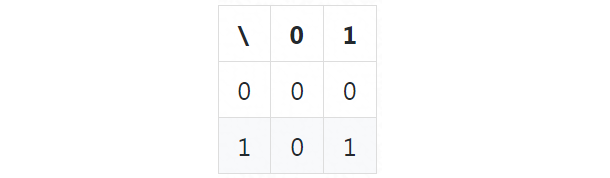

A gate is actually a truth table. For example, the truth table of an AND gate is:

In this example, the bottom-right cell indicates that if both input wires have a value of 1, the value of the output wire=1 (that is, 1 AND 1 = 1).

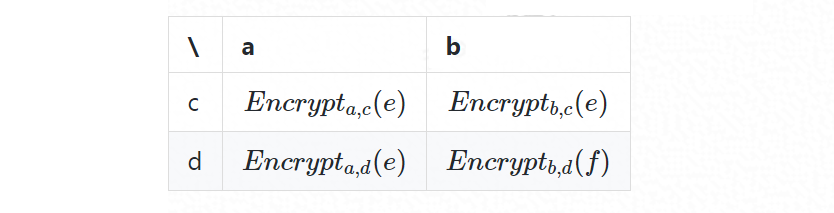

Now, assume that each wire is encrypted with a different key. The truth table now looks like this:

In this example, the bottom-right cell indicates that if the gate input is $b$ and $d$, then the gate outputs an encrypted $f$ (with the secret keys $b$ and $d$). This gate remains the same from the perspective of the control flow, the only difference is that the input and output are encrypted, and the output can be decrypted only by using the corresponding input. The decrypted $f$ can be used as the input to the subsequent gate.

It is this encryption method that is called the garbled circuit. By using this method to encrypt all the gates in a circuit in order, a function represented as a GC is achieved. This function receives encrypted inputs and outputs encrypted results.

Assume that two parties $A$ and $B$ provide data $a$ and $b$, respectively, and wish to compute an agreed function $F(a, b)$ securely. A GC-based secure two-party computational protocol process can be described as follows:

- $A$ encrypts $F$ to obtain the GC-represented function $GC_F$ (note that $A$ is the generator of the circuit, so it knows all the keys of each wire);

- $A$ encrypts its input $a$ using the corresponding wire keys in step 1 to obtain $Encrypt(a)$;

- $A$ sends $Encrypt(a)$ and $GC_F$ to $B$;

- $A$ encrypts $B$’s input $b$ using the corresponding wire keys in step 1 to obtain $Encrypt(b)$, and sends $Encrypt(b)$ to B;

- $B$ has a complete GC and all inputs, so it can run the circuit to obtain an encrypted output;

- $A$ sends the keys of the output wires to $B$. $B$ decrypts to obtain the final result $F(a, b)$;

- If $A$ requires it, $B$ then sends $F(a, b)$ to $A$.

A scrupulous reader might query why, in Step 4, $A$ encounters $B$’s input $b$. Is this not a violation of secure multi-party computation? The answer is yes – unless you implement something called “oblivious transfer”.

Oblivious transfer

Oblivious transfer (OT) can be thought of as a means of solving the seemingly impossible conundrum where two parties wish to engage in an information transfer, but are unwilling to share the index of the information that is necessary to facilitate that transfer.

Suppose that a travel agency has travel information for $n$ attractions and holidaymaker Joe Bloggs wants to visit attraction $A$. Joe wants to purchase some relevant materials from the travel agency to prepare for his trip. But he is concerned about his privacy, and does not want to disclose to the travel agency where he is going.

In other words, both parties hope that the transaction can be carried out under the following privacy conditions:

- Joe does not disclose to the travel agency the message “I am going to attraction $A$”.

- The travel agency only provides the information for attraction $A$ that Joe pays for, without revealing the other $n-1$ pieces of available information.

These conditions seem impossible to satisfy. If the travel agency exclusively provides information on attraction $A$ to Joe, it will implicitly understand that Joe is likely to visit that attraction. The only way to protect Joe’s privacy, short of him purchasing the information on all available attractions, would be for the travel agency to provide all the information to him, saving him the need to specify an attraction. But this of course runs contrary to the agency’s interests.

OT provides a way of allowing this transaction to proceed under the stated conditions. Under the OT protocol, the travel agency encrypts all the $n$ pieces of data it owns using an encryption algorithm with parameters agreed upon by both parties, and then sends them to Joe. Joe can only decrypt the data relating to attraction $A$ from the ciphertext, but cannot decrypt the remaining $n-1$ pieces of data.

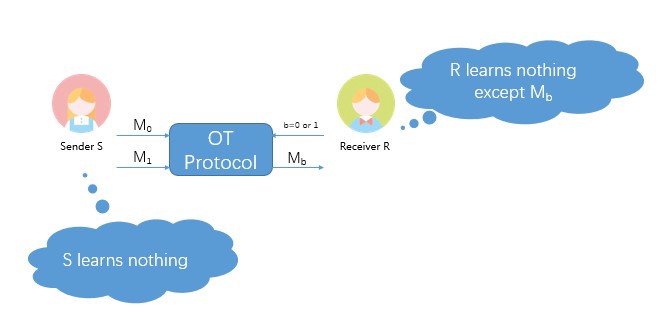

Taking $n=2$ as an example, the following figure describes a “1 of 2” OT.

One possible “1 of 2” OT solution by Chou et.al. is given below. In this example, $S$ (sender) is the travel agency and $R$ (receiver) is Joe Bloggs. $S$ owns two pieces of data ($M_0$ and $M_1$), and R hopes to obtain $M_0$.

- $S$ secretly generates a random number $a$; $R$ secretly generates a random number $b$;

- $S$ sends $A=g^a$ to $R$; $R$ sends $B=g^b$ to $S$;

- $S$ computes $k_0=Hash(B^a)$, $k_1=Hash((B/A)^a)$;

- $S$ encrypts $M_0$ with $k_0$ and $M_1$ with $k_1$: $e_0=Encrypt_{k_0} (M_0), e1=Encrypt_{k_1}(M_1)$, and then sends $e_0$ and $e_1$ to R;

- Given that $B^a = A^b$, R can obtain $k_0$ and decrypt $M^0$, but $R$ cannot compute $k_1$, hence it cannot decrypt $M_1$.

If $R$ wishes to obtain $M_1$, he just needs to revise $B=g^b$ to $B=Ag^b$ in step 2.

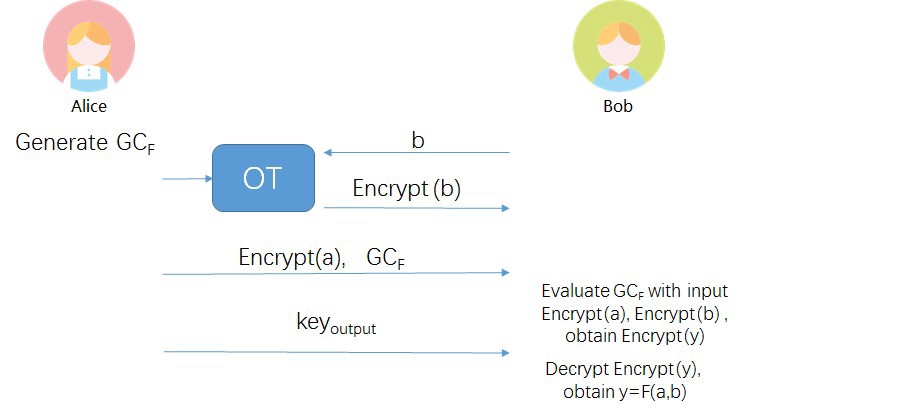

Garbled circuit with oblivious transfer

To recap the “problematic” Step 4 in the above GC computation:

$A$ encrypts $B$’s input $b$ using the corresponding wire keys in step 1 to obtain $Encrypt(b)$, and sends $Encrypt(b)$ to B;

This can be securely solved with OT, where $A$ plays Sender, and $B$ plays Receiver. $B$ obtains $Encrypt(b)$ from $A$, but does not disclose the contents of $b$ to $A$. This is summarized in the following figure:

Achieving tighter security model in Garbled Circuit

Only the basics of GC have been described above. In practice, many optimizations exist for GC, including Point & Permute, Free XOR, and Half Gates, and in recent years GC-based solutions have reached the point where they can be efficiently implemented. For example, the Hamming Distance of two million-dimensional vectors can be calculated using GC-based MPC in 1.5 seconds, with no content shared between the two interested parties.

Nevertheless, there are genuine security issues with GC, some of which can even be observed from the examples described above.

Failings of “semi-honest” GC

Keen observers may have noticed the following issue with the example given earlier: How do we ensure that the $GC_F$ that $A$ gives to $B$ is correct?

For example, assume that $A$ and $B$ want to compare two integer values $a$ and $b$, and they agreed on the function $F(a, b)=a>b?1:0$. But A could simply make another function $F’$ (for example $F’(a, b)$ output the left-most bits of $b$) that violates $B$’s privacy. And since the function is sent to $B$ using a GC, $B$ has no way to detect the violation.

This problem is one of malicious behaviors on the part of $A$. GC relies on the circuit generator conforming to a semi-honest behavioral model, whereby they will faithfully execute the procedure according to the protocol steps—at most speculating on the private data of other parties based on what they can infer. To use the analogy of a poker game, a semi-honest player might try to infer someone else’s hand from their own hand, but would still follow the rules of the game.

A malicious poker player, on the other hand, would use all means at their disposal—e.g., illegally switching their cards —to try and win the game.

Previous solutions that secure GC against malicious attacks significantly impact its efficiency. Take the Hamming distance example above, the fastest GC-based malicious security solution takes over 10 seconds, which is seven times slower than the equivalent semi-honest solution, making it hard to implement when working with large-scale data.

Malicious players do exist, however. For this reason, PVC security borrows notionally from the malicious behavior model to produce a solution that incentivizes participants to play by the rules.

The case for the PVC compromise

The key innovation in PVC is that malicious behavior is not prevented outright, but is detected by the other party in a publicly verifiable way (and so can be “punished”) with some probability $\lambda$. This $\lambda$ is called the “deterrence factor”, and incentivizes honest behavior because parties know that if they try to cheat in the protocol they may suffer a reputational loss.

Considering the importance of reputation to data owners—they may never be able to collaborate with others again if their malpractice is publicized—a 50% deterrent is considered sufficient to dissuade rational parties from wrongdoing.

PVC Perfected

The PVC model was originally proposed by scholars at Asiacrypt 2012. An improved PVC protocol was proposed at Asiacrypt 2015, but was still a long way from practical implementation.

The research team’s new PVC solution offers a concise protocol with complete code. Crucially, it does this without a major performance cost, boasting a time of just 2.5 seconds for the Hamming distance example.

Assume once again that two participants $A$ and $B$ provide data $a$ and $b$, respectively, and wish to compute an agreed function $F(a, b)$ securely. Assume also that the deterrence factor $\lambda = 50\%$. The team’s PVC scheme would work roughly as follows:

- $A$ selects two random seeds $s_1$ and $s_2$. $B$ and $A$ run OT to randomly select one of them (For argument’s sake, assume that $B$ obtains $s_1$);

- $A$ generates $GC_1$ and $GC_2$ using $s_1$ and $s_2$, respectively;

- $B$ generate some random number $c$, and run OT with $A$ to obtain the encrypted values of $c$ in $GC_1$;

- $B$ and $A$ run OT to obtain the encrypted value of $b$ in $GC_2$;

- $A$ hashes $GC_1$ and sends the hash to $B$;

- $A$ hashes $GC_2$ and sends the hash to $B$;

- $A$ signs all the above process transcripts and sends the signatures to $B$;

- Since $B$ has $s_1$, it can generate $GC_1$ by itself, and can simulate Steps 3 and 5 by itself. If the result is inconsistent with that sent by $A$, the relevant signature is published as evidence of the malicious action of $A$. If they are consistent, $GC_2$ is used for true computation.

If $A$ acts maliciously, there is always a $\lambda=50\%$ probability of being caught out by $B$, because $A$ does not know which GC seed is in $B$’s hand. Therefore, a rational $A$ would choose not to act maliciously, and would instead implement the MPC protocol faithfully.

We note again that this article only deals with the relevant technical concepts on a very basic level. Interested readers can learn more by reading the full paper.